Communication Measures to Bridge 4.543 Billion Years – GeoWeek at the University of Cumbria Institute of Arts

Last week I met with many heartily missed friends at UoCIoA to deliver this brief introduction to The Man Who Fell to Millom…

In 2018 I was commissioned by Irene Rogan, Director of the Moving Mountains Festival (in Millom, Cumbria) to make a film about the operational Ghyll Scaur Quarry. However, after visiting the quarry and Millom, I somewhat ignored the brief and produced the 14-minute film The Man Who Fell to Millom – a short, atmospheric work set in Millom which uses cut-up and collage techniques to suggest an alternative dystopian narrative for the post-industrial coastal town. At the festival, the film was shown on a large screen from the stage of Millom Palladium, a privately owned but community-run, and slightly dilapidated theatre space – with an excellent PA.

Situated on the West coast of Cumbria, crucially outwith the border of the Lake District National Park, Millom has a bleak beauty. It is a scarred landscape which has been used and abused over a long period. It used to be lined with shipyards, coal mines, iron-ore workings and factories, but these have now closed, leaving behind a weary location and a relatively isolated – geographically and economically – community. The neighbouring Furness Peninsula has some of the earliest human settlements identified in the UK – people have been living and working in Millom since the end of the ice age. Above Millom, is Giant’s Grave – two standing stones which bear cup and ring marks.

Today, the Sellafield Nuclear Processing Plant is a source of employment and sits 15 miles north of Millom and the UK’s nuclear submarine fleet is serviced nearby at Barrow. It was this rich industrial past and nuclear present which intrigued me on my site visits to Millom, far more than the single operational quarry which was already attempting to cater to visitors with its Millom Rock Park – ‘a geological visitor attraction’.

However, as a Glasgow-based artist commissioned to make a film about a Cumbrian town, I was acutely aware of my outsider status. Working with sound artist Mark Vernon, my approach was to imagine discovering Millom – its rich industrial past and its people – as if I were an alien, sifting through and weaving together audio and images that I found in the ether.

Unusually, there was a clear division of labour when making The Man Who Fell to Millom as Mark and I were on different continents while we were researching and making. Mark created a soundscape which I then used, unedited, as the framework on which to build the visual elements of the film. Mark’s soundtrack aims to span millions of years, beginning in pre-historical times and moving to present day Millom – in just 14 minutes.

Using a collage technique and images appropriated from the Net, I worked to Mark’s original soundscape, piecing together what you might be able to call a science fiction narrative for the town of Millom, haunted by the poetry of Millom resident Norman Nicholson.

Nicholson was born in Millom in 1914 and lived there until he died in 1987. His poetry has, at its heart, the visual and emotional collision between idyllic scenery and industrial vigour which became, after the closure of Millom’s iron-ore mine and associated smelting works, an industrial wasteland over his lifetime. In his poem On the Closing of Millom Ironworks of September 1968, Nicholson writes:

Wandering by the heave of the town park, wondering

Which way the day will drift,

On the spur of a habit I turn to the feathered

Weathercock of the furnace chimneys.

But no grey smoke-tail

Pointers the mood of the wind. The hum

And blare that for a hundred years

Drummed at the town’s deaf ears

Now fills the air with the roar of its silence.

They’ll need no more to swill the slag-dust off the windows;

Nicholson also wrote that every child in the community ‘is joined by an umbilical cord, stretching back through the ooze, to the shelled, creeping creatures of the warm lagoons.’ (NN in Principle Pleasures, 1959, reprinted 1993 in Norman Nicholson: The Whispering Poet, Kathleen Jones, 2013). In her 2013 book Norman Nicholson: The Whispering Poet, Kathleen Jones says that ‘Time for Nicholson was not linear – the past and the present were there in every moment of his life, in everything he saw and touched. […] When he talked about his early life, memory and imagination fused to produce their own narrative truth.’

The Man Who Fell to Millom gathers textures of the Cumbrian landscape, both rural and industrial, memories of its people and the developing, contradictory sounds of nature and technology, of geology and the digital.

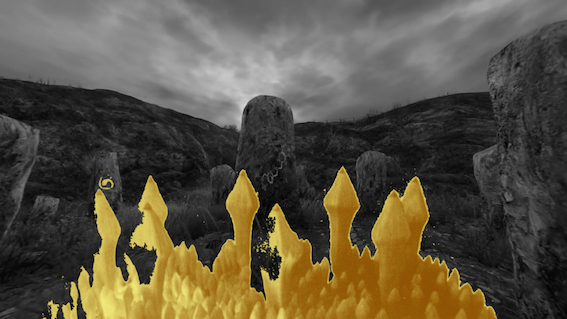

Beginning on a calm shoreline, the film tells the absurd tale of a creature – perhaps awakened by iron ore mining – and the humanoid that opposes it. The viewer follows in the footsteps of a hooded figure, literally a man who fell to Earth (because the figure is David Bowie in Nicolas Roeg’s 1976 film TMWFTE), as he walks a rocky coastal landscape and navigates a towering slagheap, pursuing the ominous presence which seems to threaten the past inhabitants of Millom.

The opening scene in Nicolas Roeg’s The Man Who Fell to Earth, in which the alien Thomas Jerome Newton played by David Bowie tentatively negotiates a coal hill, was shot in New Mexico, in the then ghost town of Madrid. Like Millom, Madrid is a former mining town and its visual and economic similarities to Millom were one reason I made a visual connection between the two post-industrial landscapes in my film.

Another reason my film references Roeg’s so directly is that I’m a fan of the film and of Roeg’s work in general. In the Forward to Susan Compo’s 2017 book Earthbound: David Bowie and The Man Who Fell to Earth, editor of the film Graeme Clifford writes that:

Nic [Roeg] has always regarded the slavish adherence to ‘plot’ to be largely unnecessary. […] Consequently, his movies require more attention and concentration on the part of the viewer. In fact he regards the audience as a participant in the movie. As in life, one doesn’t always understand what is happening or why at any particular point in time. So it is in Nic’s movies. But if you allow yourself to be immersed in what is going on, rather than becoming frustrated by trying to figure it out right then, his movies become more accessible.’ (2017)

Bearing this influence in mind, The Man Who Fell to Millom is atmospheric and mimetic and its Cthulhu-like creature might embody the Cumbrian industrial past or nuclear present. Paying homage to Roeg’s directing style, the film plays with notions of time and is more concerned with creating an atmosphere and experience of the post-industrial nuclear coast than a linear narrative. Within the film, a fragment of Nicholson’s poem Shingle (1981) offers layers of texture – of grey waves, of stone and of butterbeans.